Background

Following on from my previous article on problem solving, I would like to share some practical advice based on my personal experience working for a software publisher. Here, the problems encountered are bugs (or anomalies) in each delivery. This feedback comes from a Scrum team made up of developers known as integrators and a tester responsible for adapting software for an end customer. This customisation of generic software is carried out using Java code to meet the specific needs of the end customer.

As is often the case, we start with an unsatisfactory and, above all, rather confusing situation, in this case, late deliveries. This delay is due to the fact that the team spends a lot of time correcting anomalies, and that this lost time is not spent developing the expected customisations (= features). This is an apparent cause but not the root cause, which we will come back to shortly. The schedule becomes very tight, even almost unachievable, as the delay accumulates with each iteration. When I asked the team how they were managing this delay, they told me about staffing issues: the team needed to be strengthened (the classic solution…), with additional developers and testers brought in to make up for lost time.

That’s when I try to find out more and ask more questions, particularly about quality.

How is the quality of what we deliver?

Answer: … ?

How many defects need to be corrected with each delivery?

The answer varies between:

A little / Quite a lot, actually / I don’t know, but it’s in Jira!

As is often the case, no one has a clear idea of the number of quality issues (anomalies, bugs, etc.). I therefore suggest applying the problem-solving approach to this situation.

Plan – First step: clearly define the problem

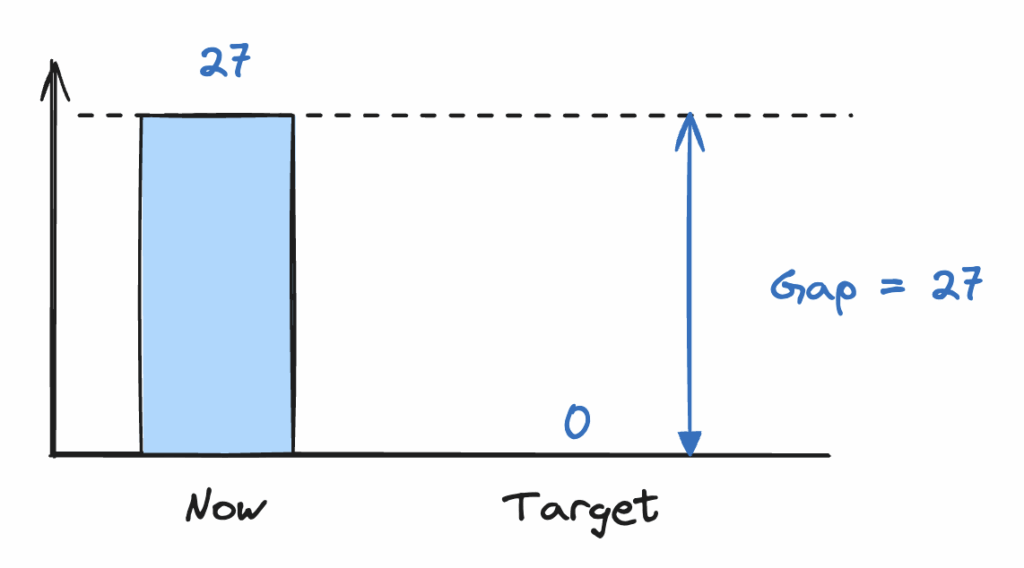

As you now know, a problem is a gap and must be measured. After a few filters and Jira exports with the team, we obtain a number of tickets: 27 bug tickets detected during testing over the last three sprints.

Bingo, we have our gap and our target:

The impact of this lack of quality is clear: while the team fixes these 27 bugs, it falls behind on delivering the settings expected by the client.

- Impact on the customer: late delivery of the project -> customer dissatisfaction

- Impact for the publishing company: late penalties -> To be quantified

- Impact on teams: the tester begins to get annoyed by the quality of the deliverables, which they find very poor -> stress, deteriorating working atmosphere.

It is recommended to accurately quantify the financial impact (calculation of late fees, loss of project margin due to time spent fixing bugs, etc.), even though we have not done so in this example. Nevertheless, given the impact observed in our situation, we can deduce that it may be worthwhile to invest at least a few hours with the team on this quality issue.

Let us now turn our attention to the causes.

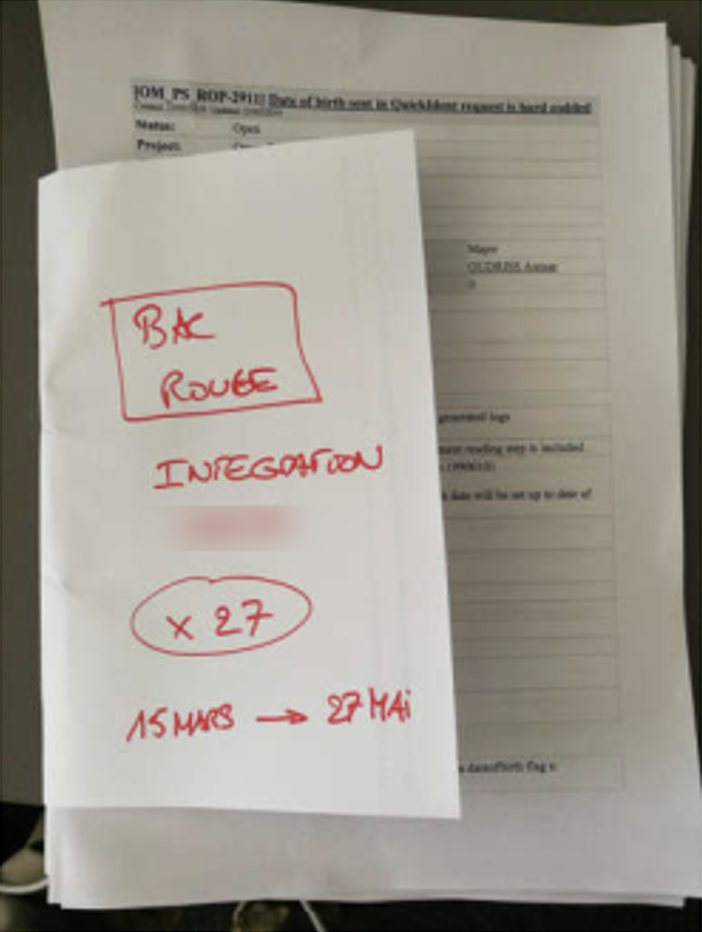

I suggest that the team take advantage of their one-hour Scrum retrospective with three developers and one tester to examine the problem more closely. We then analyse the 27 tickets that were printed beforehand. In lean manufacturing, these defects are called red bins, defective parts that are placed in a red bin for later analysis.

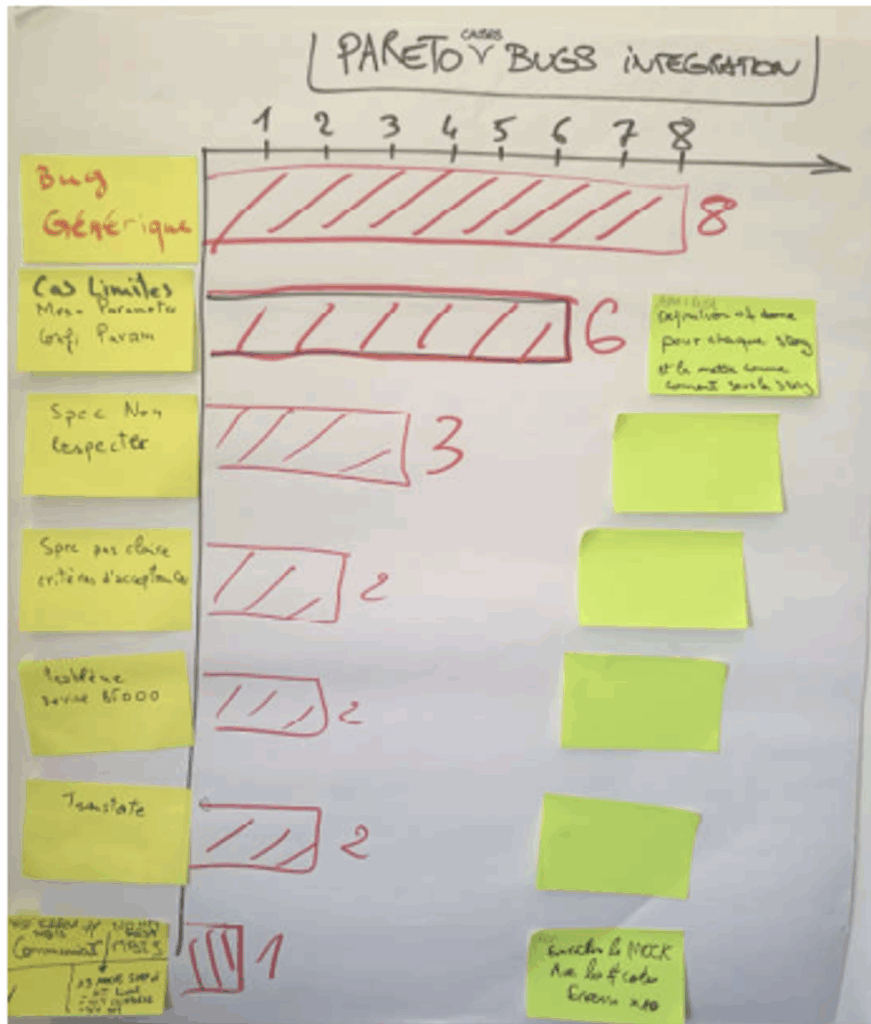

These defects are grouped by cause family to construct what is known as a Pareto chart in order to highlight the recurrence of certain causes. ⚠️ It is important to note that we do not group by bug category (UI bugs, translation bugs, performance bugs, API bugs, etc.), but rather by cause: for each anomaly, we look for the cause(s) and count the number of times they appear.

We then decide to focus on the four most common causes (Pareto head):

8 occurrences of Generic product bugs (cause #1). As the Generic product is developed in the USA, our team of integrators does not have the authority to modify the product directly. We will therefore need to send the product teams a ticket requesting a fix so that they can take this into account in a future version of the product. At first glance, our team does not have the authority to take action on this cause.

6 occurrences of edge cases (cause #2). The code developed does not withstand certain edge cases. Why? Because developers do not have all the different expensive external devices (cameras, fingerprint readers, etc.). Instead, they use « mocks », which are a kind of code plug that emulates these external devices. The problem is that these mocks do not cover edge cases (approx. 10 error codes to simulate). On the other hand, the person in charge of testing has all of these devices and can therefore detect them.

Three instances of specifications not being followed by developers (cause #3). The developers admit that they skimmed through the specifications a little too quickly, missing a few key points that were clearly stated in the initial ticket.

2 instances of ambiguous specifications (cause #4). Upon reviewing the last two tickets, it appears that the specification was indeed ambiguous enough to leave room for doubt as to what needed to be developed.

Now that we have identified the root causes, it is time to move on to countermeasures to improve the situation.

Do – Time for action

I am now asking the teams what we could do to improve the situation in each of these areas.

For cause #1 on the Core product, an integrator developer still feels able to fix certain bugs because he already has access to the source codes. He suggests asking the Core team if he could be allowed to modify the product code himself, since he knows how to fix it. Although this is formally « prohibited by the process », after a few exchanges with n+1, n+2, and n+3 over the following weeks, the request is granted on the condition that peer reviews (code reviews) are carried out by a Core developer in the USA. Ultimately, this will save both teams several weeks of work by removing a critical dependency.

For cause #2 concerning edge cases, I am asking one of the developers if they have any ideas.

Answer: We could add 4 or 5 new edge cases to the mock to cover the 10 missing error codes.

And how long would that take?

Answer: About 10 minutes per error code!🙂

For causes #3 and #4 concerning unread or ambiguous specifications, the developers, product owner and tester agree to conduct a shared review before starting each new feature in order to remove any ambiguity and ensure that the developer has fully understood the purpose. The tester proposes to systematically add all the test cases they will perform to the Jira ticket.

The next sprint will be an opportunity to try out each of these countermeasures: nothing revolutionary, but precise adjustments to certain actions and to the handover between team members (product owner/developer/tester).

Check – Does it work?

For the next sprint, the team first decided that it would be useful to track the number of bugs more closely and to have a performance indicator that could be checked every day. They also collectively decided that quality was everyone’s responsibility. One team member was tasked with building the indicator, and each day a different person was responsible for updating it. They then discussed it during the daily meeting.

At the end of the next sprint, the result is impressive: no bugs reported by the tester! The team congratulates itself and enjoys this first small victory.

Of course, this is only the beginning. Other anomalies will therefore arise during future sprints (new causes of bugs, personnel changes, etc.), but the team now knows how to address each of these issues through a demanding and rigorous approach.

Act – What did the team learn?

For the team and the team leader, their main lesson was understanding that improving quality speeds up delivery. This was an opportunity for them to break out of the so-called Quality / Cost / Delivery triangle, where you are asked to choose two and give up on the third. This is false, yet so ingrained in people’s minds: the reality is that by improving quality, you improve lead times and costs.

For developers, this is an opportunity to better understand the level of requirements expected of the product they are developing, particularly in terms of code robustness in extreme cases: a camera suddenly disconnected, a loss of network connection, etc. They also realised the importance of meeting customer expectations down to the smallest detail: there is no room for improvisation or ambiguity. Delivering good code on the first try is not that easy, but it is possible: bugs aren’t fatal !

The team will also present this new retrospective practice to their colleagues in the open-plan office, providing an opportunity to share and reflect on the progress made.

Pitfalls to avoid

- For you, as a tech leader: avoid pushing your solution. It is important to let teams come up with ideas to test. Your role is to ask questions (why, how could we do things differently), encourage, and as a last resort, if nothing comes from the team, then suggest something to try.

- Avoid silver bullets: « And at OpenAI, it seems they’re doing… »

- Avoid magic tools: if a tool could prevent bugs, everyone would use it.

- Beware of experts (the « superheroes« ) who tend to overwhelm the rest of the team with their experience. If they were good coaches for their colleagues, quality would have been a more important issue for a long time.

Conclusion

In just one hour of applying the problem-solving approach, we drastically change the situation by mobilising the entire team on the issue of non-quality through a rigorous and pragmatic problem-solving approach.

This example also challenges the somewhat dogmatic views that are sometimes expressed: « Do you use Scrum or Kanban/Lean (choose your side 🙂)? ». It can be effective to use your own in-house Software Development Life Cycle, and to introduce problem-solving practices that will enable teams to be much more precise in improving quality. Ideally, you should address the issue as soon as it arises.

How do you run your continuous improvement retrospectives? How do you encourage your teams to challenge themselves on the quality of the code delivered in order to strive for the ideal of 100% Right First Time?

Laisser un commentaire